Using Bloom’s Taxonomy with stories to help children develop cognitive skills

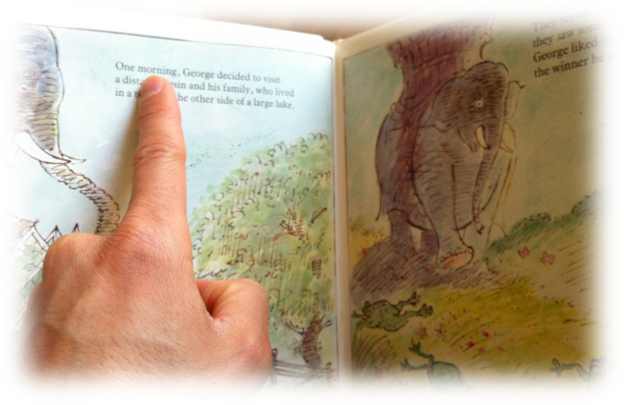

I heard about Bloom’s Taxonomy a while ago and I decided to look into it to see how I could apply it to reading stories with my daughter and try to devise ways of helping her develop her cognitive skills.

I am hoping that this article will give you an insight into what Bloom’s Taxonomy is and provide some simple ways you can use it when reading children’s stories with your kids. Essentially, I’m hoping that by the end of this article you will :

- Have an idea of what Bloom’s taxonomy is and why it is useful

- Have some ideas on how you can help your kids build their cognitive skills by using some simple questions when sharing a children’s story together.

As a parent, I want my daughter to be able to think for herself, form and defend opinion and forge her own path in life. Understanding what is involved in performing that kind of attitude and thinking and knowing how to help her develop those abilities is another way I reckon I can do my best as her Dad.

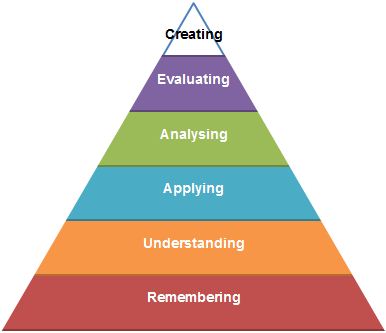

What is Bloom’s Taxonomy?

Bloom’s Taxonomy is one of the most widely used references in education and, over the years, has even been translated into 22 different languages and is in use around the world.

Psychologist Benjamin S. Bloom was known for contemplating and extensively studying the process of how things worked and this included the process of “thinking”.

He believed that there was specific behaviours that could be noticed and were important in the in the process of learning and in 1956, Bloom’s Taxonomy was created.

There are actually three different domains that make up Bloom’s Taxonomy:

- Cognitive – Mental skills and Flexibility (Knowledge);

- Affective – Growth in Feelings or Emotional capacity (Attitude)

- Psychomotor – Manual or Physical skills (Skills).

Each domain is then segmented into different levels for educational goals and objectives.

The Cognitive Domain of Bloom’s Taxonomy

The “Cognitive” domain is what is focused on when helping children learn how to read and think and this is what teachers put a lot of emphasis on in schools.

It is also the focus of this article and, if people would like to know more, I might follow up with the other domains in separate articles (so please do let me know in the comments).

Bloom’s Cognitive domain focuses on the knowledge, comprehension and critical thinking that a child uses or displays during reading time.

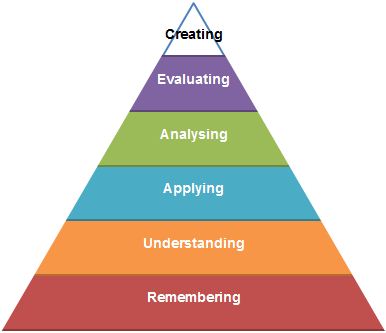

Bloom created six different levels of cognitive learning and suggested that each level must be mastered before the child can move onto the next level.

In the 1990’s, a former student of Bloom’s revised the Taxonomy which brought it into the 21st century and it was again updated in 2001.

The only thing altered in the revision is the names of the levels which now look like this:

Every child’s critical and cognitive thinking starts with the lowest level and gradually works up to the highest level

There are definite signs that a child shows when they have mastered each level and there are specific questions that you can ask of your kids which will encourage the mental stimulation needed to obtain the next level.

Here is a quick guide for each level that shows the signs a child might exhibit when they have mastered it and example questions that can be asked to encourage mental growth.

By noticing the child’s reactions and answers you will be able to tell when the child has reached a new level in learning and reward accordingly.

To give us a children’s story base line, I am using Little Red Riding Hood as the example book we’re reading. It is important to note that this applies throughout childhood and adolescence and arguably, we never stop developing these levels, so if you have a 4yr old, a 10yr old or even a stroppy teenager, you can and should still apply all of these idea.

Bloom’s First Level : Remembering

In this level the child will be able to recall basic facts about the book through memorising and be able to answer general questions about the book or objects that are in the book.

Help your kids master the remembering level by asking questions like :

- Who is Red Riding Hood going to see?

- What is little Red Riding Hood wearing?

- What did she have in her basket?

If you were reading the Gruffalo for example, you could encourage them to remember the rhythm and rhyme of the story.

Bloom’s Second Level : Understanding

At this level, our kids will be able to understand the main idea of the book, recognise characters and organise the facts.

Ask questions such as :

- Why was Little Red Riding Hood walking through the woods?

- Why did the wolf put on Grandma’s clothes?

These questions will help your child master understanding of the situation and concepts in the book.

Bloom’s Third Level : Applying

At this level, our kids should be able to show that they can use the knowledge and facts acquired from the book and apply it to other situations.

Ask questions such as :

- Besides going through the woods, how could Little Red Riding Hood have made it to Grandma’s house?

- Why is it dark in the woods?

- What would happen if Red Riding hood had gone with a friend?

These kind of how and why and what if questions will encourage your kids to apply what they have learned from other aspects in life equipping them with the ability to do it at any time.

Bloom’s Fourth Level : Analysing

This level encourages the mind of the child to examine the facts of the book, distinguish differences and gather evidence to support what they think.

Questions around the ideas of :

- Why is walking through the woods alone dangerous

- If you were Little Red Riding Hood what would you do?

These kind of questions make your child concentrate on the scenario to gather important facts which will lead to a conclusion.

Classroom debates at school are specifically designed to develop this analysis and reasoning ability and having constructive discussions from different positions on a topic is a skill that’s well worth encouraging.

Make a game of it and challenge your kids to argue a counter position to an opinion they hold dear – Why Pop music is a bad influence, or why mobile phones should be banned from use at school for example. Make it fun and tongue-in-cheek (this is very important).

One of the many anti-bullying techniques used in schools in the uk is to have kids arguefroth for and against the motivations of a fictious classroom bully.

Bloom’s Fifth Level : Evaluating

In this level the child will learn how to evaluate the evidence that they use to draw their conclusion and justify or defend their opinion on the story.

To encourage the development of this cognitive skill, ask opinion questions such as :

- Do you think it was wrong for the wolf to try to trick Little Red Riding Hood?

- Do you think it what the wolf tried to do was fair?

Get your kids to justify their opinion by asking them why they think it was wrong or fair etc.

For older or moore developed kids: ask them whether they think there were any mistakes or assumptions made by the author (or screen writer if discussing a film). Where there any inconsistencies in the opinions or actions of the characters or story?

For those at exam age, these kinds of critical evaluative discussions often take the form of English or Science homework.

Bloom’s Sixth Level : Creating

In my opinion, this is perhaps the most fun level and because of that I think it’s actually easier than some of the earlier ones.

At this level, our children will be able to gather the information they have learned and create an alternative ending or construct a new scenario for the story.

Encourage the child to write a poem or song from the story or maybe have Little Red Riding Hood on the moon.

It is up to the child’s imagination what they develop from the story because the basis has already been set up through the original story.

—

I just want to point out that while there are 6 levels, it is in fact a sliding scale and kids will develop different skills at different levels at different times, and you will also notice how each level stacks on top: requiring our children to use the skills developed at the lower levels in order to be able to develop the new ones.

Other bonuses of asking questions about a children’s story you’re reading together

As my daughter and I have discovered, there are all sorts of other bonuses from making this part of story time!

We have great little games where I ask question after question until she makes a big dramatic show and goes “Daddy, enough questions!”.

We make up alternative stories from scratch which leads to all sorts of adventures and games. It also gives me a chance to guide the story to deliver other morals or lessons.

Boring books and stories suddenly become more interesting as you explore possible made up back stories to the characters’ and situations and believe me : your kids will come up with some weird and wacky ideas!

—

A good Google session will reveal all sorts of articles and resources on this, but don’t get bogged down with trying to learn all there is to know. The best thing you can do for your kids is to learn a little bit and give it a go with them. If you want a quick reference guide, then chthout this PDF which gives both hints at the kinds of words to be using as well as suggested questions and outcomes to aim for when following the taxonomy.

Whatever you do, enjoy story time. It should be fun and not “work” or a chore or else our kids won’t enjoy it. They’ll soon tell you they’ve had enough!